Dia de Independencia (Independence Day) was my introduction to over-the-top holiday celebrations in Mexico. I had just moved to Mazatlán and my furniture hadn’t arrived yet. I carried a sauce pan, a frying pan, and a few plastic dishes in my luggage. I bought a small bed, a tiny outdoor table and two plastic chairs at Sam’s Club. I went to the used appliance store and bought a stove and a refrigerator. I had enough to survive but I wanted my stuff.

My moving truck was stalled at the border because the inspector found a package of new sheets in one of my 250 boxes. Because I couldn’t prove that I paid sales tax in the U.S. for the sheets., I had to give the inspector $200.00 to approve my move across the border.

I know it was a bribe. I know the bribe cost more than the sheets were worth. I was lucky. He didn’t open the box that contained the digital grand piano. That didn’t have a receipt either.

Truly, I felt trapped that day, September 16, 2005, as I watched Neto and his friends install a fountain in my courtyard. There was nothing I could do until the moving truck arrived.

And then I heard a police siren announcing a parade. The most wonderful parade I’d ever seen.

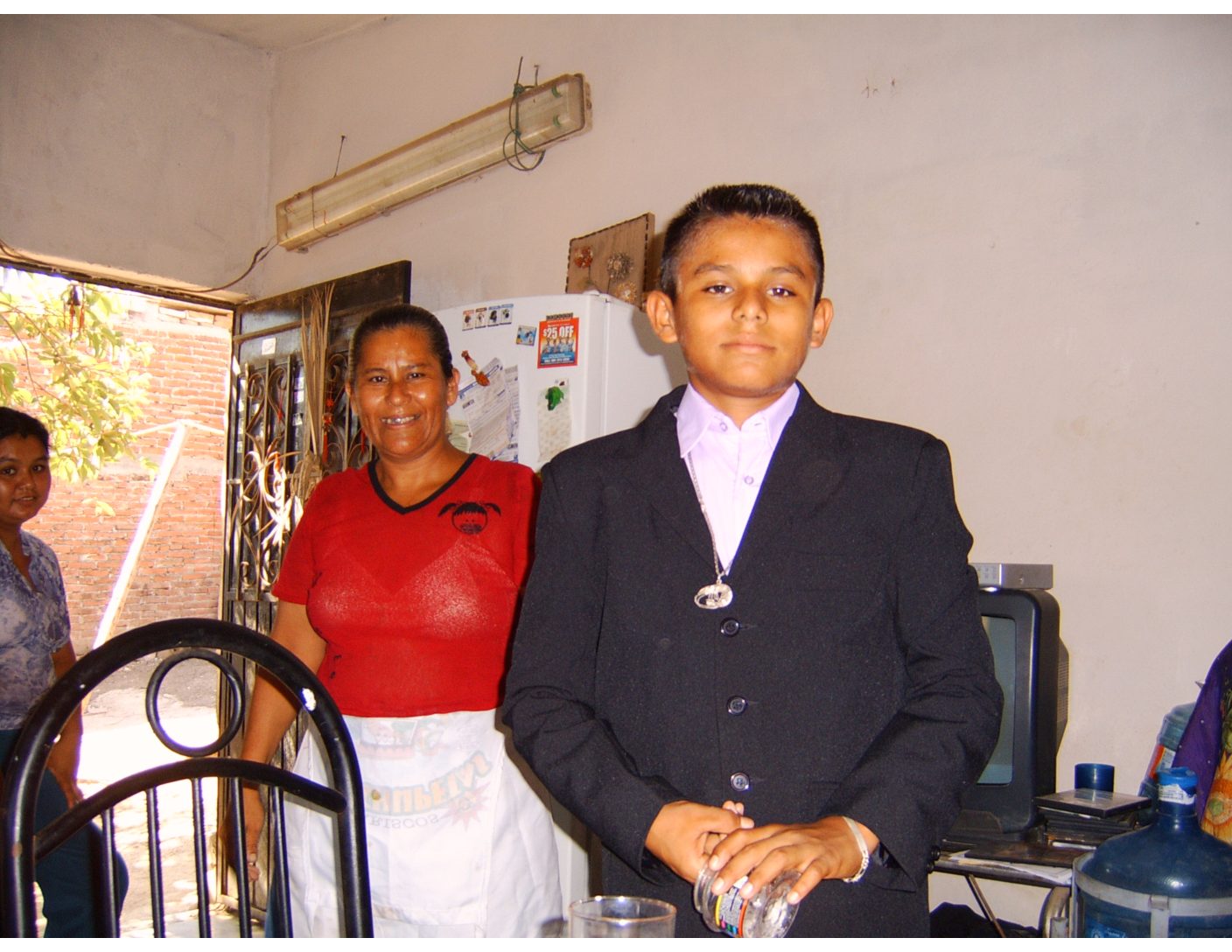

To the beat of drums and music blaring from huge speakers on top of cars, little children came walking down my street, holding hands, dressed as guerrilla warriors from 1810. Preschool boys and girls, with bullet belts and long skirts, walking with their teachers. Unbelievably cute!

That’s when I knew I made the right decision. My home was right on the parade route. For the next five years, I watched every parade, (and there are a lot of them!) from my plastic chair placed right in front of my door.

Día de la Independencia marks the moment when Father Miguel Hidalgo, a Catholic priest, made his cry for Independence. His chants, ¡Viva Mexico! and ¡Viva Independencia¡ encouraged rebellion and called for an end to Spanish rule in Mexico.

The Spanish regime was not prepared for the suddenness, size, and violence of the rebellion. From a small spontaneous gathering at Father Hidalgo’s church in Delores, the army swelled to include farm workers from local estates, prisoners liberated from jail, and a few soldiers who revolted from the Spanish army.

Farmers used agricultural tools to fight. Rebel soldiers had guns and bullets. Indians, armed with bows and arrow, joined the cause. The revolution rapidly moved beyond the village of Dolores to towns throughout Mexico.

Father Hidalgo was captured and executed on July 30, 1811. Father José Maria Morelos, a seminary student and friend of Father Hidalgo, took charge. The movement’s banner, with an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, was symbolically important. She was seen as a protector and liberator of dark-skinned Mexicans. Many men in Hidalgo’s forces went into battle wearing the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe on their clothes. The War of Independence was won on September 27, 1821.

Much like the Fourth of July in the U.S., Mexicans celebrate their country’s Independence Day with fireworks, parties, food, dancing and music. Flags, flowers and decorations in the colors of the Mexican flag – red, white and green – are seen everywhere in cities and towns throughout Mexico. Whistles and horns are blown and confetti is thrown to celebrate this festive occasion. Chants of “Viva Mexico” are shouted among the crowds. And school children, dressed in Mexican themes, march through the streets of their neighborhood.

The following day a moving truck with all of my belongings pulled up in front of my house. Out jumped six strong, handsome Mexican men, ready to unload everything. Boxes containing everything I thought I would need and some things, like Christmas decorations and recipe books, I wasn’t yet ready to part with. And my piano!

¡Viva Mexico!

Neto and I were having lunch at a busy restaurant across from an old railroad station when Zapatista arrived at our table, carrying a large, leather-wrapped jug of homemade pulque. We invited her to sit down at our table and talk to us. She was tired. Her feet were sore. She was happy to spend some time sitting at our table. But first we bought a glass of pulque.

Neto and I were having lunch at a busy restaurant across from an old railroad station when Zapatista arrived at our table, carrying a large, leather-wrapped jug of homemade pulque. We invited her to sit down at our table and talk to us. She was tired. Her feet were sore. She was happy to spend some time sitting at our table. But first we bought a glass of pulque.