Two huge mango trees in my Mazalán courtyard. A source of welcome shade throughout the year and wonderful fragrant blossoms beginning in January. By spring the trees were heavy with delicious sweet mangoes. Thousands and thousands of mangoes! More mangoes than one person could eat or even dispose of without a plan.

But Neto had a plan. He hung a sign on the door that said, “Free Mangoes!” and invited anyone walking down the street to ring the doorbell, come inside and help themselves. I didn’t realize that Lola and Julio, my next door neighbors, wouldn’t like what I was doing.

First Lola pleaded with me to ban the neighborhood children from coming into the courtyard. She wanted me to put mangoes in bags and hand them out the door, as if it were Halloween.

That way, she reasoned, no one would know what my courtyard looked like. Her exact words were, “You don’t know what you are doing. These kids are bad. They are surfers!”

Lola told me that even the police were angry with me for opening my courtyard to children coming from the beach. When I told her that I would be careful but I intended to continue to give away free mangoes, I thought she would explode.

Later that day, Neto and Publio were up on the rooftop picking mangoes when Julio came to the open window that overlooked my house. He started screaming at them.

“You are looking in my window! Stop looking and me! Stop looking at me”

Julio picked up a fallen mango and pitched it right at Publio’s head so hard it could have killed him. Luckily, Julio, drunk as usual, missed. Publio, who is generally very passive, said that if he’d gotten hit he would have just started pitching mangoes right back at the old fool. And by that time, Publio had an arsenal of more than sixty mangoes at his disposal.

I wish I had used that opportunity to tell those two busybodies to close up their windows and they wouldn’t have to worry about people looking in or climbing through the windows to rob them. Of course, then they couldn’t watch what I was doing, either.

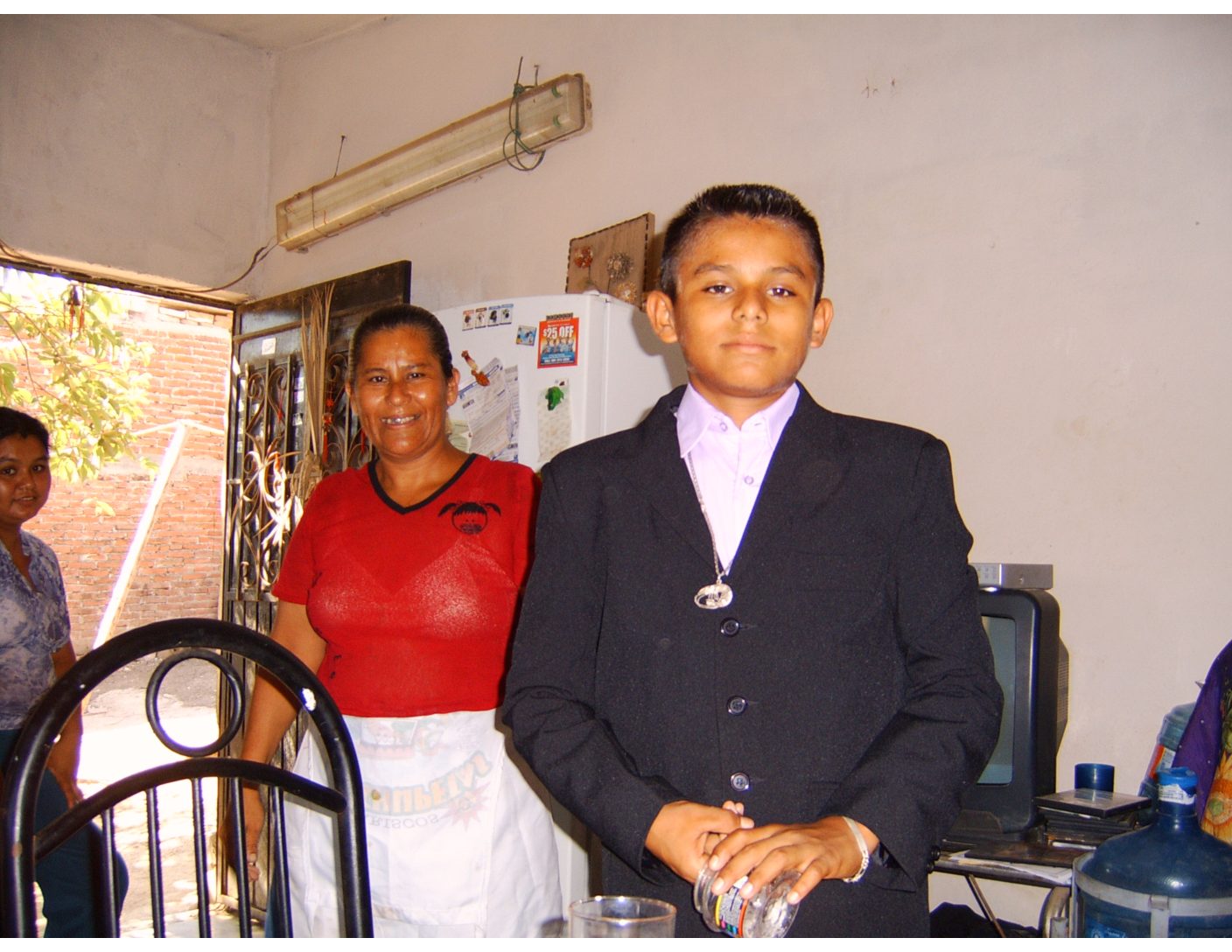

Soon whole families were at my door, holding plastic bags. Word spread throughout the neighborhood about our ripe, juicy, free mangoes. We brought the families inside and turned on the music. There was dancing and laughter in the courtyard. There was a party goin’ on!

One Saturday, after a week-long Mango Fiesta, my doorbell rang about 2:00 in the afternoon. I opened the door to find two uniformed policemen standing there. I remembered what Lola said and figured they were there to arrest me or, at least, warn me about the dangers of opening my door to children.

Before I could say anything, one of the policemen pulled a plastic bag out of his pocket and asked, “Are you still giving away free mangoes?”

“Por supuesto! Of course!” I said. “Here, use this ladder to get on the roof and pick all the mangoes you’d like.”

“And,” I added with a smile, “Come back any time.”

Neto and I were having lunch at a busy restaurant across from an old railroad station when Zapatista arrived at our table, carrying a large, leather-wrapped jug of homemade pulque. We invited her to sit down at our table and talk to us. She was tired. Her feet were sore. She was happy to spend some time sitting at our table. But first we bought a glass of pulque.

Neto and I were having lunch at a busy restaurant across from an old railroad station when Zapatista arrived at our table, carrying a large, leather-wrapped jug of homemade pulque. We invited her to sit down at our table and talk to us. She was tired. Her feet were sore. She was happy to spend some time sitting at our table. But first we bought a glass of pulque.